Did that sound good? This is the question I most often ask when I listen to children read. In this blog, I discuss what fluency is and some ways to grow fluent readers.

What is reading fluency?

Due to the focus on fluency research and instruction during the past couple decades, it is widely understood that fluency is more than just the rate at which one reads. Kuhn and Rasinski (2015) stated, “We would argue that fluency is one of many important components in skilled reading, and its instruction is a valuable element of the literacy curriculum when placed in the proper perspective” (p. 269). They are referring to what has happened in some instances when there is too much attention placed on accurate reading, as this leaves the other components of fluency behind. These other components are prosody, pausing, phrasing, stress, and intonation (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017). Successful reading that sounds good occurs when readers orchestrate all these together, along with rate.

It is helpful to remember that text choices for guided reading can support or hinder fluency. Fountas and Pinnell (2017) reminded us that background knowledge, text content, text organization, and genre are contributors to fluency. The more readers know about a text, the more fluent their reading will be. Knowledge of language is also a factor in fluent reading, as, “for the young reader, knowledge of syntax is probably the most powerful system for supporting fluency” (p. 426).

Automaticity

I sew for a hobby. Imagine if, every time I sewed, I had to focus all my attention on each step: threading the bobbin and needle, placing my fabric, putting my foot to the pedal, cutting stray threads, etc. The process would be so long, exhausting, and laborious that I wouldn’t want to do it anymore! This applies to the reading process, as well.

LaBerge and Samuels (1974) wrote about the concept of automaticity, or the ability to perform a task while devoting little time to each individual detail of that task. If students are hyper-focused on reading every word correctly by articulating every phoneme, for example, they are not freeing up their attention to gain meaning from the text. Readers need to “do problem-solving against a backdrop of accurate reading” (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017, p. 427). Being able to quickly recognize what they know makes problem-solving on the run easier for especially emergent, early, and even transitional level readers. As teachers, it is our job to move them from laborious decoding to “effortless” and “automatic” work on text (Kuhn & Rasinski, 2015, p. 270).

Discourage Slow Reading

I’ve spent many hours in classrooms over my 20-year career observing strong and gifted practicing teachers and teacher candidates. Despite their good intentions, however, I’ve heard children engaging in “slow reading.” Clay (2005) cautions, “At no time…should the child be a slow reader of the things he knows” and that teachers are not to “accept slow, staccato, word-by-word reading (p. 151, emphasis hers). While it is acceptable for readers to read new or challenging texts at a slower rate than independent or instructional level text, most of the reading during the school day (shared reading, guided reading, independent reading time) should be texts that children can control (i.e., independent reading with easy familiar texts and shared reading, which is highly teacher-supported). While some children definitely struggle with prosodic reading at an acceptable rate, what is evident is that some of the problems occur when the teacher gets in the way! Sometimes, unintentionally, we send the message that “getting the words right” is the most important part of reading a book. We encourage this “slow reading” by:

- frequently interrupting the child each time a word is read inaccurately.

- doing drills (timing exercises where students create graphs, etc.) that bolster this and actually reward children for correct word reading (Clay).

Accuracy

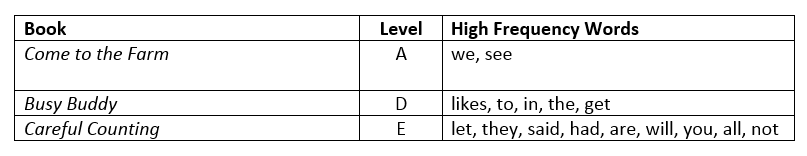

Accuracy, of course, has to be considered when discussing fluency. Being able to quickly recognize words, word parts, and letters is essential to fluent reading. Fortunately, many companies that produce books for guided reading instruction publish books that are leveled according to a text gradient (i.e., Fountas & Pinnell guided reading levels A through Z). Each level contains more complex visual (referring to letters and words) information than the level before, allowing for the “build-up of fast responding to known vocabulary” (Clay, 2005, p. 150). Here are some examples of high frequency word presentation in three Red Rocket Reader books. Notice how more high frequency words are included with each jump in text level. Children need to build up their repertoire of known words since the number they meet in texts will grow exponentially along the way.

Rate

Rate

It has been established, of course, that rate is not the lone force in reading fluency (thank goodness!). Yet, many programs continue to isolate it and give it a lot of attention. While we want to be careful not to overemphasize rate for children, it is necessary, in some cases, to explicitly teach for a quicker, livelier pace. Clay (2005) even has a prompt for this for the child who seems to plod along: Can you read this quickly? She also recommended a procedure, one that I have used from time to time in Reading Recovery lessons, guided reading lessons, and individual reading conferences.

“Slide a card from left to right over the text, forcing the child to speed up so he can process a little more fluently…this encourages him to make his eyes work ahead of his voice” (Clay, p. 153).

Here is a short video that demonstrates this procedure:

Phrasing

When we speak, we naturally group words into phrases. We do the same thing when we write, using punctuation or just the natural flow of language to signal to our reader when to pause. If a reader is to fully understand an author’s message, they need to group words together that the author has meant to go together (Clay, 2005). Here are several ways to “draw students’ attention to reading in meaningful phrases” (Kuhn & Raskinski, 2015, p. 272).

- Use the prompt, Put these words together so that it sounds like talking (Clay, p. 152).

- Demonstrate how to read text in phrases by masking the text with a card and exposing a few words at a time.

- Mark phrases directly in text with highlighter tape or with pencil on copies of text, considering where phrasing would be most natural.

- Here is an example of the Red Rocket Reader What Feels Cold? (Level B). Notice that, in this text, the lines are formatted to provide a high level of support for phrasing.

- Page 2 – The snow / feels cold.

- Page 4 – The wind / feels cold.

- Page 6 – The ice / feels cold.

- Here is an example of the Red Rocket Reader I Can’t Whistle (Level D). In this text, the lines are longer and the reader must do more of the phrasing work.

- Page 2 –

“I can whistle,” / said the train.

I can whistle / at the cars.

Can you whistle / like me?

- Page 2 –

- Here is an example of the Red Rocket Reader What Feels Cold? (Level B). Notice that, in this text, the lines are formatted to provide a high level of support for phrasing.

Prosody

No one enjoys listening to robotic reading! Children love to listen to their teachers perform rich renderings of books. We want students to emulate that reading when they read out loud and when they read silently. Practice is necessary in order to master prosodic reading. Prosody involves using expression, pitch, tone, and emphasis on certain words and syllables to make the reading sound good. Kuhn and Rasinski (2015) said “readers who incorporate prosody provide evidence of an otherwise invisible process, that of comprehension” (p. 270). In other words, it’s usually difficult to read something with the prosody that the author intended without also understanding the text. Two prompts Clay (2005) advised to use with readers who need a little push in this area are: Make your voice go down at the end of the sentence and Change your voice when you see these marks on the page.

We often see elementary school-aged children in our reading clinic at the university who display disfluent tendencies. One such child, George (pseudonym) was reading the Red Rocket Reader, Fox’s Cave, a level I folktale about a fox who tries to lure several animals into his cave. The fox coaxes each animal with, “Come into my cave for breakfast.” While listening to George’s reading of the text with his tutor, I heard him read Fox’s line in a monotone voice. I immediately stepped in and chatted briefly with him about what was happening in the story and asked him to tell me what Fox was trying to do. George understood the story well enough, but seemed shy when I asked him to read the line like Fox might say it to get the animals to enter the cave. So I modeled how the reading should sound and requested that he repeat it and continue on in this manner. What a difference this made!

General strategies

Here is a (partial) list of tried and true instructional strategies to implement to address fluency:

- First and foremost, keep the balance of attention on language and meaning in continuous text (Clay, 2005).

- Provide many opportunities for students to read at all levels of difficulty.

- Select texts that facilitate fluent reading (songs, poems, repetitive texts, etc.)

- When introducing the text, review unknown and partially known words, as well as any difficult “book language.”

- While students are reading, only interrupt as needed and be brief!

- Use a “fluency phone” so that students are better able to listen to themselves

- Use echo reading – “Listen while I read this.” “What did you notice?” “Now you read it like I did.”

- Sometimes, it may be advisable to drop the level of text to support fluent reading.

Helpful prompts (Clay):

- Are you listening to yourself? Did it sound good?

- Make it sound like a story you would love to listen to.

Assessment

Assessing fluency is a fairly easy task! All a teacher needs to do is take a sample of a student’s oral reading and listen closely. “There is no substitute for listening to a segment of oral reading, and there is no other way to determine the degree to which readers can reflect the meaning of written language with their voices” (Fountas & Pinnell, 2017, p. 423). Zutell and Rasinski (1991) developed the Multidimensional Fluency Scale, which measures all dimensions of fluency (expression and volume, phrasing, smoothness, and pace) on a four-point scale. This way, teachers can zone in on areas which need strengthening.

Happy reading!

Bethanie

References:

Clay, M.M. (2005). Literacy lessons designed for individuals: Part two: Teaching procedures. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fountas, I.C., & Pinnell, G.S. (2017). Guided reading: Responsive teaching across the grades (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Kuhn, M.R., & Rasinkski, T. (2015). Best practices in fluency instruction. In L.B. Gambrell & L.M.

Morrow (Eds.), Best practices in literacy instruction (5th Ed.) (pp. 268-287). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S.J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, 293-323.

Zutell, J., & Rasinski, T. (1991). Training teachers to attend to their students’ oral reading fluency. Theory into Practice, 30, 211-217.

Like what we've got to say? Spread the word!