Assessing and Teaching Children in the Area of Phonological Awareness

My pre-service teachers often confuse the terms phonological awareness, phonemic awareness, and phonics, so we spend a good amount of time on each and how they are related. I offer precise definitions and instructional examples, which helps to clear up the muddy waters! Phonological awareness is the “awareness of sounds in words in learning to read and spell” (ILA Literacy Glossary, 2018). It encompasses the hearing of syllables, onsets and rimes, and individual phonemes. Phonemic awareness is “the ability to detect and manipulate the smallest units (i.e., phonemes) of spoken language” (ILA Literacy Glossary, 2018).

Because phonological awareness predicts decoding, it also affects reading fluency and comprehension. Lundberg et al. (1988) asserted that early instruction in the areas of phonological and phonemic awareness had a substantial influence on reading and writing achievement. They indicated that instruction should be explicit and fast-paced.

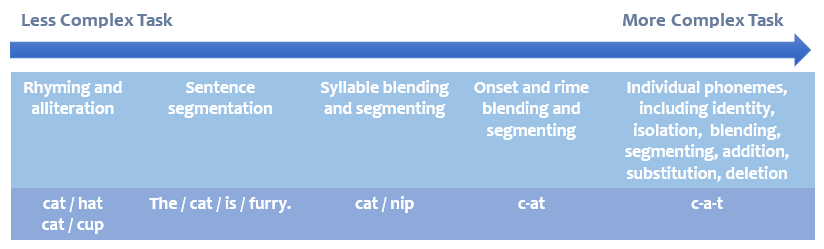

There also exists a continuum of phonological awareness skills, and teachers need to be cognizant of these because expecting a child to delete the initial sound of a word and replace it with another sound is substantially more difficult than breaking apart the syllables in a word. Here is a table, based on Liberman et al.’s (1974) work that I frequently share with preservice and practicing teachers.

In an article on early literacy research, Reutzel (2015) discusses how some strategies have been determined to be more effective than others for increasing phonological and phonemic awareness. He suggests that teachers should devote more time to the following: blending (saying /c-a-n/ and asking the child to blend the sounds together), segmenting (saying /cat/ and asking the child to break apart the phonemes), and manipulating phonemes (asking the child to take /c/ off of /can/ and say what the word would be if they added /m/) and less time to rhyming (can, man) and alliteration (can, cup) activities.

Virtual phonological awareness assessment strategies are similar to those conducted in person. There are a myriad of phonological and phonemic awareness assessments available. The gist of most of these are that they ask children to blend, segment, add, and delete phonemes. The teacher simply meets with the child one-to-one virtually and clearly states the directions of the task and the spoken words on which the child is to take action. One thing to consider is that the child should be able to hear you clearly, so you’ll need to make sure that your microphone works well and perhaps ask the child to wear headphones.

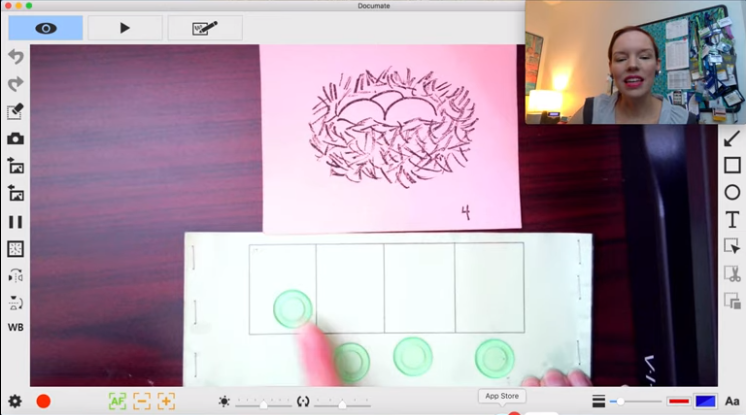

Whenever I teach my undergraduates about or provide professional development on phonological awareness, Elkonin boxes (sound boxes) are always included in our discussions. Elkonin boxes allow children to hear phonemes in words, which will later help them to read and write words because they will be able to hear all the parts. Clay (2005) provides clear instructions for working with sound boxes.

- The teacher first models saying the word slowly and naturally (not artificially segmented).

- The child must then do the same.

- During this procedure, the sounds in the word will become more evident.

- Beginning with picture cards is helpful. I have pictures of the following words: egg, pie, tie, fan, pig, sock, lamp, hand, and nest.

- It’s important to remember that, during this process, no letters are used yet – that will come later. At this point, it’s all about encouraging the child to listen for sounds.

- The teacher then draws the boxes during this procedure as a scaffold. Therefore, it’s crucial that teachers have a clear understanding of how many phonemes are in a given word (e.g., cat has three phonemes; chat has three phonemes; egg has two phonemes; tie has two phonemes; float has four phonemes).

- It is better to demonstrate this procedure without a lot of talk. I usually say, “Watch as I push in a counter/penny/button each time I hear a sound.”

- The teacher says the word in the picture, stressing any hard-to-hear sounds, and asks the child to do the same, asking them to “say it slowly.”

- Next, the teacher models the task by saying the word very slowly and pushing the counters/pennies/buttons into the boxes. I always emphasize that we use one finger – the index finger of our writing hand.

- The teacher then encourages the child to try it together. T

- The teacher can also share the task by saying the word as the child pushes the counters/pennies/buttons and having the child say the word while you push the counters/pennies/buttons.

- The child then completes the entire task themselves. I usually begin with several words that have two phonemes, and work my way up to three and four phonemes.

Teaching this process virtually is very similar to teaching it in person. In the video attached to this blog, I used a document camera and placed the materials needed underneath to facilitate clear examples. All the child needs to do is draw the number of boxes needed on a piece of paper and locate four counters/pennies/buttons. This video is meant to be a pre-recorded one that children could watch on their own. The process could look the same during a live virtual lesson.

Happy Reading!

Bethanie

References

Clay, M. M. (2005). Literacy lessons designed for individuals: Part Two. Heinemann. International Literacy Association. (2018). Literacy Glossary. https://www.literacyworldwide.org/get-resources/literacy-glossary

Liberman, I. Y., Shankweiler, D., Fisher, F. W., & Carter, B. (1974). Explicit syllable and phoneme segmentation in the young child. Journal of Exceptional Psychology, 95(3), 482-494.

Lundberg, I., Frost, J., & Peterson, O. (1988). Effects of an extensive program for stimulating phonological awareness in preschool children. Reading Research Quarterly, 23(3), 263-284.

Reutzel, D. R. (2015). Early literacy research: Findings primary grade teachers will want to know. The Reading Teacher, 69(1), 14-24.

Like what we've got to say? Spread the word!