During the many hours I’ve spent in elementary classrooms over the past 20 years, it is rare that I see children just reading. Real readers don’t work on worksheets or participate in long blocks of phonics practice – they read. They read books and manuals and recipes and articles on news websites. If we want children to be readers, we need to teach them how readers behave and what readers do. Fountas and Pinnell (2016) assert that all activities in the balanced literacy classroom need to include reading continuous text. This can occur during read-alouds, shared reading, guided reading, and independent reading and helps children “develop a self-extending system for processing texts” (p. 18). Teachers often complain that children are not reading enough at home. If “time spent reading feeds more reading” (Miller, 2009, p. 50), then why is there not more time devoted to reading during the instructional school day?

Why continuous text?

There’s a great story line on an episode of Friends where Joey asks Phoebe to teach him to play guitar. She refuses to let him touch the guitar, however, and instead first teaches him what his hand looks like as he makes each cord. After he tires of this practice, he sneaks behind her back, buys a guitar, and begins playing! This is a perfect example of how, in order to learn something, we have to actually do it. Fisher et al. (2019) call it the “practice effect…the more a student reads, the more words she will be exposed to” (p.163 ). It’s important to note that all children need practice reading, and teachers should use instructional time wisely in order to maximize time spent reading, not just doing activities about reading (Allington, 2011; Fisher et al., 2019).

Reading practice builds fluency and motivation and helps students apply all that they are learning in whole and small group instruction (Fisher et al., 2019). Children need this practice to integrate what they know about letters, words, and sounds so that they can find meaning in a piece of text (Clay, 2019). Teachers need to hear children read continuous texts so they can informally assess what cueing systems they are attending to and what they are neglecting. The teacher who teaches children words and letters for most of the school day and doesn’t allow for extended times for children to practice reading can be likened to Phoebe teaching Joey just the isolated basics of playing the guitar!

The old “drill and kill” method of teaching is back in schools, thanks to many of the current Science of Teaching Reading misunderstandings. Teaching some skills in isolation is fine, but proceed with caution (Routman, 2018)! Don’t overdo it because we don’t want children to think this is what reading is all about – knowing sounds, letters, and words in isolation. When you do teach items on their own, always go back to the text and apply it because we want children to engage in reading at the “level of the story” (Clay, 2007, p. 100). This warning appears throughout Marie Clay’s work as she reminds teachers that children have “to learn the letters and the words, and their relationships to sound, but [they] also [have] to build and expand the intricate interacting systems in the brain that must work together at great speed as [they] read text” (2007, p. 102).

Continuous text in guided and independent reading

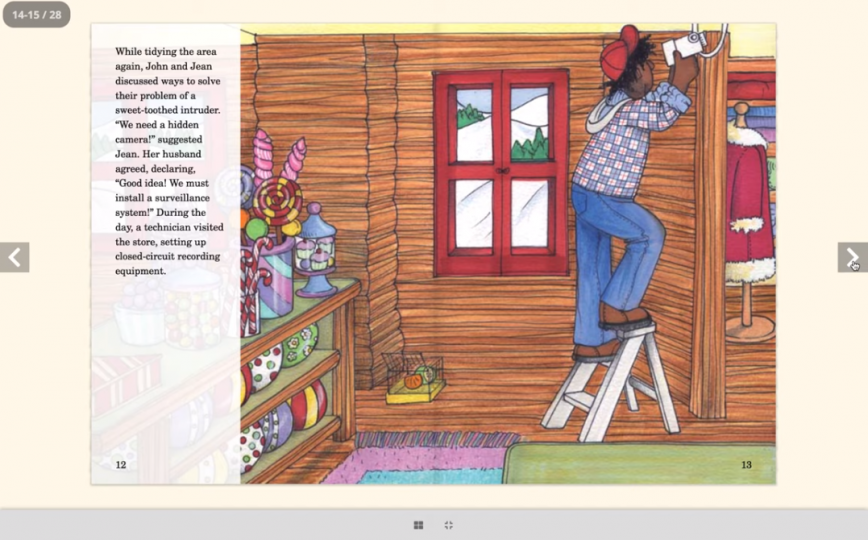

The definition of guided reading includes the reading of continuous text. It is during guided reading instruction that children learn strategies to apply “on the run” (Clay, 2007). Young children are also able to build a sense of story during guided reading if the teacher uses little books that contain narratives told from beginning to end. Only having the child read part of the text would deprive him of this experience. During guided reading instruction, it is the child who is in control and doing most of the reading work, and the teacher is the “guide on the side” (Routman, 2018, p. 218). By listening to the child read, the teacher is able to informally assess the child’s use of decoding and comprehension strategies and can harness this information to scaffold and prompt the child in order to lift his reading.

Allington (2011) gives many reasons why children need to have long chunks of time to read. Fisher et al. (2019) echoed this in their recent book, This is Balanced Literacy. They remind us that students need to build their reading stamina by reading books they have chosen. This independent reading time, however, isn’t just a time when students sit and read. The teacher needs to monitor the reading and hold frequent reading conferences with students because “deliberate practice without effective teaching and coaching doesn’t guarantee growth” (Routman, 2018). Teachers who sacrifice this time to take care of other instructional tasks should reconsider this move and remember that children need time to apply what they’re learning in real reading contexts. Donnalyn Miller (2009) says, “The question can no longer be ‘How can we make time for independent reading?’ The question must be ‘How can we not?” (p. 51).

This link will take you to a video of a prerecorded lesson on summarizing a text with the Somebody Wanted But So Then strategy, a great strategy to use after reading a continuous text during a guided reading lesson.

Happy Reading!

References

Allington, R. L. (2011). What really matters for struggling readers: Designing research-based programs (3rd Ed.). Pearson.

Clay, M. M. (2007). Literacy lessons designed for individuals part one: Why? when? and how? Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (2007). Literacy lessons designed for individuals part two: Teaching procedures. Heinemann.

Clay, M. M. (2019). Observation survey for early literacy achievement (4th Ed.). Heinemann.

Fisher, D., Frey, N., & Akhaven, N. (2019). This is balanced literacy: Grades K-6. Corwin.

Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2016). Guided reading: Responsive teaching across the grades (2nd Ed.). Heinemann.

Miller, D. (2009). The book whisperer: Awakening the inner reader in every child. Jossey-Bass.

Routman, R. (2018). Literacy essentials: Engagement, excellence and equity for all learners. Stenhouse.

Like what we've got to say? Spread the word!