Why is Familiar Reading Important?

“The practice of reading familiar books encourages confidence and fluency and provides practice in bringing reading behaviors together (orchestration), but it also allows the reader to discover new things about print during the rereading” (Clay, 2005, p. 98).

This part of the guided reading lesson is sometimes referred to as a “warm-up,” and it may serve that purpose; however, it is so much more than that!

- Why not start off the guided reading lesson with a text that helps children feel successful? It’s okay that these texts are easy – they should be within the children’s reach.

- This successful second reading also helps to build a repertoire of strategies. The more practice to solidify new strategies the children have, the better.

- Since the text is familiar, it is easier for readers to work on emerging behaviors. There is not too much work to do, which allows room for them to show what they know!

Familiar reading should sound natural. The books used for this portion of the guided reading lesson shouldn’t be memorized. While these are fine (to an extent) for independent reading, what you’re looking for is a book that has been read once, maybe twice, as a new book during the prior lesson. Books that the children have memorized will not offer enough opportunities for problem-solving. What should result from this experience are renderings that are fluent and accompanied by solid comprehension. It’s also important that the teacher is present to prompt, reinforce, and teach while leaving space for the children to problem-solve. Such a balance to strike! This is where the teacher’s fine-tuned discretion and knowing the readers come into play. Intervene only when absolutely necessary.

Running Records: What, Why, and How

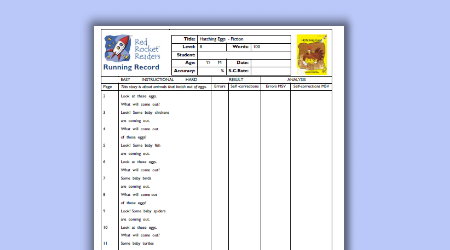

The best definition of a running record is quite precise – it is a “true account” of a child’s oral reading of a text (Clay, 2013, p. 55). Afterwards, the teacher writes an overall reaction to the reading and shares a teaching point with the child, offering immediate feedback.

Why take running records? Why would you not?! Here are some reasons to take running records:

- You’re able to note reading progress by documenting what your readers do on text and you can “plot a path to progress” (Clay, 2013, p. 53) on a chart for each child.

- Quantitatively scoring frequent running records helps to determine the level of text difficulty for each child and you can then make adjustments accordingly.

- Running records help to guide your teaching and determine what to teach next based on patterns of reading behaviors. Remembering that all attempts are partially correct, you assess how the reader is pulling together what he or she already knows about letters, sounds, and words and make decisions to “extend the beginning reader’s literacy learning” (Fried, 2013, p. 5).

- Running records provide a window on your teaching and help you examine what you are doing that is helpful and what might be missing in your instruction. “If teachers take records of text reading with a wide sample of children they will quickly discover which things are emphasized and neglected in their class instruction” (Clay, 2013, p. 81).

- Documenting reading progress assists you to flexibly group and regroup your students for guided reading instruction.

Teachers frequently ask me, “When do I administer running records?” Clay (2013) wrote, “A classroom teacher should, ideally, be able to sit down beside a child…and take a running record when the moment is right. Teachers should practice until it is as easy as that” (p. 55). So, when is the moment right?! You’ll know! You’ll get to know your readers and decide how frequently and at what point during the instructional day works best.

The teacher and child sit closely, side-by-side. It’s a casual event, something the child should be used to if reading for the teacher occurs frequently. The teacher neutrally listens to the child’s reading and does not intervene unless absolutely necessary, usually to give a “told.” In this case, the child is unable to proceed because she is aware she has made an error and cannot correct it or does not make an attempt at the word. The teacher also quickly makes notes about fluency and other notable behaviors.

While taking a running record, I usually circle any areas to which I might return after the reading. This way, I’m prepared to make an immediate teaching point. This might be to address a miscue or some successful solving that is new. Before making the teaching point, however, it’s important to have a brief conversation with the child to do a quick check on comprehension (Clay, 2013). Later on, I quantitatively score the running record to find an accuracy rate and a self-correction rate. I then take a qualitative look at the sources of information the child used at points of difficulty. Fried (2013) suggested that teachers also review the running record for self-monitoring, high-frequency word reading, problem-solving actions, and “tolds.” I also pay close attention to patterns, both within this one running record and across other recent running records.

Miscue Analysis

Since no help is to be given during the running record, we are able to see what moves the reader makes (or doesn’t make) on their own. When evaluating miscues, a good rule of thumb is to look at how “the miscue disrupts the meaning of the written material” (Goodman, 1972, p. 32) and then hypothesize what might have caused the child to make that move. The child’s oral reading of the text serves as a window into their thinking. This analysis takes time, as it should, as “quick judgments regarding readers can be harmful and lead to mistaken judgments” (Goodman, p. 37).

The “Told”

I recently reread an article about the running record written by Mary Fried (2013). My new take-away was what she wrote about the “told.” Tolds are one of the three responses that teachers may provide during a running record administration. The teacher waits about three seconds and gives the word, indicating this as a “T” on the running record. “This preserves the storyline and starts the reader off again” (Clay, 2013, p. 60). Fried (2013) pointed out that tolds are just as important as miscues because they give you “insights into what you should be teaching” (p. 11). The analysis of a running record should include asking yourself why you decided to give the told. Obviously, children who have more tolds during a rereading of a text are those who may need more reading support. Sometimes, children have learned to wait for a told, rather than having been taught how to problem-solve.

Additional Thoughts on Running Records from the Research

In an article titled “Revisiting the Role of Miscue Analysis,” McKenna and Picard (2006) recommended that teachers continue to use running records to determine reading levels. They explicitly warn, however, that the use of “semantically acceptable miscue tallies” is not effective. Teachers should instead view these miscues as “evidence for inadequate decoding skills” (p. 379) and encourage students to use decoding to drive their reading.

In Fawson et al.’s (2006) study, a Reading Recovery-trained literacy specialist trained first grade teachers to administer running records. The teachers then video-recorded their running record administrations with several Level 14 texts with each first grade student and used the recordings to score the records. The major finding was that there was some inconsistency in student performance on each of the texts written at the same level. The implications are that teachers should listen to a student read several passages at one text level in order to obtain a “true reading level” (p. 124).

All Red Rocket Reader titles have free downloadable Running Record forms. They are beautifully formatted and easy for teachers to use. Hopefully this blog entry will help you to view running records in a fresh light.

Happy reading (and running record-taking)!

Bethanie

References:

Clay, M.M. (2005). Literacy lessons designed for individuals: Part two: Teaching procedures. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Clay, M.M. (2013). An observation survey of early literacy achievement (3rd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Fawson, P.C., Ludlow, B.C., Reutzel, D.R., Sudweeks, R., & Smith, J.A. (2006). Examining the reliability of running records: Attaining generalizable results. The Journal of Educational Research, 100(2), 113-126.

Fried, M.D. (2013). Activating teaching: Using running records to inform teaching decisions. Journal of Reading Recovery, 13(1), 5-16.

Goodman, Y.M. (1972). Reading diagnosis – qualitative or quantitative? The Reading Teacher, 26(1), 32-37.

McKenna, M.C., & Picard, M.C. (2006). Revisiting the role of miscue analysis in effective teaching. The Reading Teacher, 60(4), 378-380.